On the Surreal Realism of Ottmar Hörl's Photo Concepts

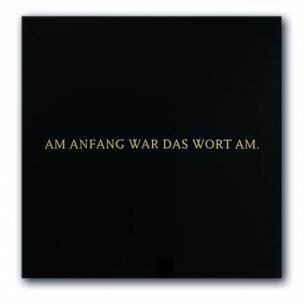

"We try to create order in ourselves as well as we can, but this order is only something artificial ... The natural ... it's chaos."

Arthur Schnitzler, The Vast Domain, 1910

The dichotomy of chaos and order is as old as Adam and Eve – it begins with the expulsion from paradise. The culture of "wild thinking" as experienced by Claude Lévi-Strauss (La pensée sauvage, 1962) must have been paradisiacal. Fascinated by the cultures without writing, the ethnologist describes the ways of thinking of the indigenous people, which are based on their habitat, nature-adapted traditions, holistic orientation and mythical world view. Lévy-Strauss postulates that our "tamed thinking" is by no means superior to "wild thinking": the "primitive" is not driven by instinct instead of reason, but does not process more concrete material less sensibly – but simply differently – but with different goals and more strongly in the mode of "bricolage". This brings us to contemporary art – namely the Neue Wilden, proclamically the Dadaists, compositionally the Fluxus, behaviorally the Art Brut, experimentally the Ready Made. And currently to Ottmar Hörl.

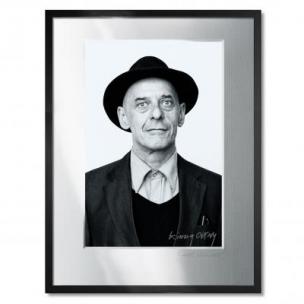

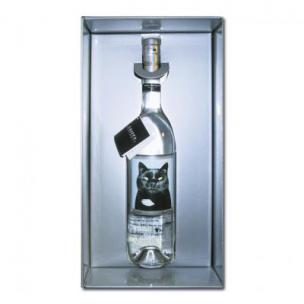

Ottmar Hörl defines sculpture as working with the material of one's time, i.e. one's own living space. In his eyes, contemporary sculpture can be object art, painting or photography (with this credo he occupied the chair at the Academy of Fine Arts in Nuremberg from 1999 to 2018). His material world includes a wide variety of "objéts trouvés" – not only building materials, everyday objects, traffic signs, tools and instruments, but also cameras.

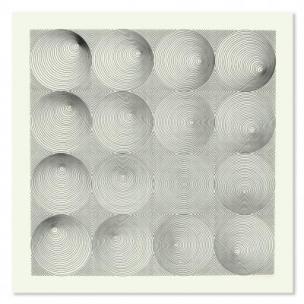

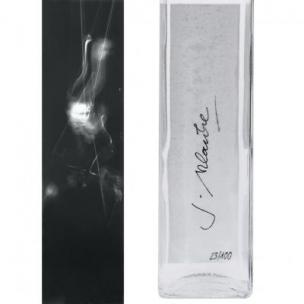

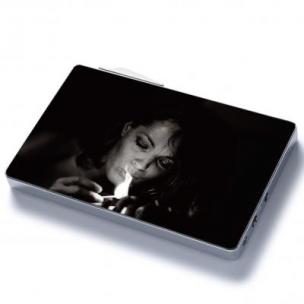

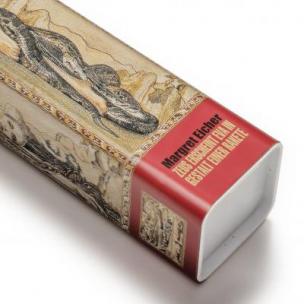

Since 1982 he has been throwing SLR cameras equipped with a film transport motor, set to 2.5 car clicks per second, from skyscrapers, television towers, cable car gondolas, airplanes, mounting them on car wheel rims and cordless screwdrivers. His creative ambition is limited to triggering the production of random and ultimately captivating images that rotate horizontally or wobble at 220 km/h in the free fall of the natural force of gravity as if by themselves – while the self-triggering cameras "reach the limits of their existence as tools" (Hörl). Until they land, however, the flying cameras describe curves and figures that the sculptor Hörl regards as interacting sculptures.

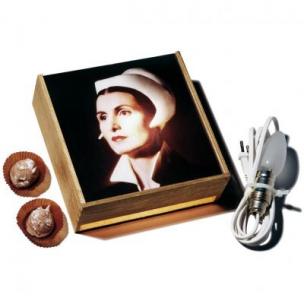

In this "organisational principle that defines itself above and through space" (Hörl), the artist combines reality and the world of possibilities, tradition and development potential, habitat and fantasy – the imaginative use of buildings, means of transport and utensils without following their obligatory functional dictates. He creates the leap from order to chaos, the balancing act between Homo technicus and Homo ludens – in order to bring the random result back into a formal order that corresponds to his aesthetic feeling as Homo faber. Chronologically ordered, cleanly elaborated, laminated or framed picture series are created in rhythmic wall and room installations. Also a "moral picture of the late 20th century", which Hörl creates by giving loaded cameras to all households in a suburb of Frankfurt with the task of photographing "what is most important to them" – except people (Götzenhain 1999). With such rationally planned actions, Hörl achieves ratio-free results, unencumbered by the creative will that dominates the visual arts. Autogenerated results that are perfect without the corrective of "tamed thinking". In the spirit of Lévi-Strauss' Wild Thinking.

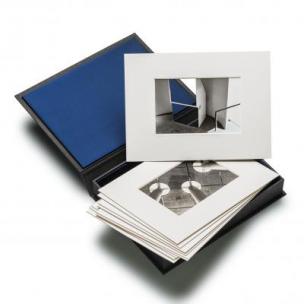

The portfolio edition "Wild Thought" gathers a selection of ten photographs in the part "Rotation (Photography)" that Ottmar Hörl brought home from an expedition through the forests of the Spessart in 2011. These "second sculptures" were created with a digital camera mounted on a cordless screwdriver and rotating at 3.5 frames per second. Its pictorial style is related to his most recent painting cycles "Coldplay" (2018) and the series of paintings represented in the portfolio section "Il Mare (Painting)". In Il Mare's painting process, Hörl (as a sculptor he does not paint with a brush, but with his hands in acrylic on canvas) limits himself in terms of time in a similar extreme way to photography, in order to exclude cognitive reflections or creative transformations: In a five to ten second staccato, a stroboscope of around 200 large individual images is created.

In Ottmar Hörl's blurred painting style, Gerhard Richter's early squeegee images echo, in his camera drop and rotation photographs Richter's blurred renderings of reality from newspaper images – time-displaced according to their biographical distance of two decades. In the sense of time of both artists, the world turns faster and faster. Due to the increasing frequency with which the images rush past us, they become blurred in our eyes. In artistic processing, the event image becomes an image event and the experience image an image experience.

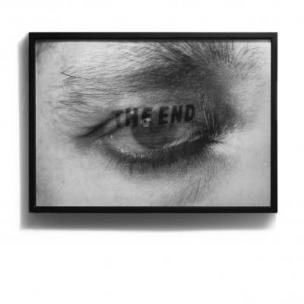

Hörl's rotation images correspond to the increasing rotation of current events. A dynamization that he felt at the beginning of the 1980s and presented in his photographic projects as an offer of perception. An acceleration that today takes place in nanoseconds – i.e. about a billion times faster than biological neurons – in forward transactions and exponential algorithms. The resulting loss of control is the central criterion in Ottmar Hörl's visual concepts.

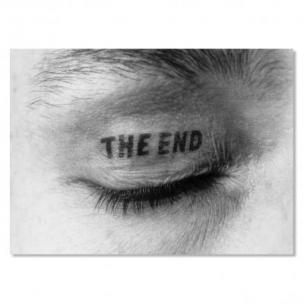

"Because I only ever photographed what I had seen before, I had to change my method": in order to find new pictures, Hörl, who regards himself as the "greatest uncertainty factor" in photography, was no longer allowed to look through the viewfinder. He obviously knew his Matisse: "The photographer should interfere as little as possible, otherwise every objective charm photography possesses according to its nature will be lost". It is in the nature of the artistic handling of photography that its "artificial order" (Arthur Schnitzler) is transposed into an ordered chaos – from realistic surrealism to surreal realism. From "wild thinking" (Claude Lévi-Strauss) to counterproductive action. Who would have thought that it is in the lens of the released Hörl cameras that the subjective eye of the beholder – one and a half centuries after Daguerre – is still surprised and carried away.

"One can approach the physical world from two opposing points of view: from an extremely concrete or an extremely abstract one; either from the point of view of sensually perceptible qualities or from the point of view of formal qualities.“

Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Wild Thinking, 1962

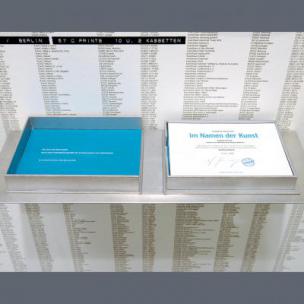

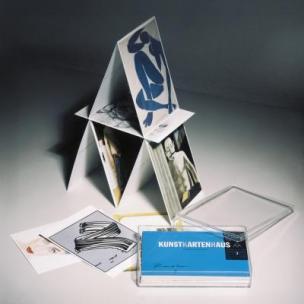

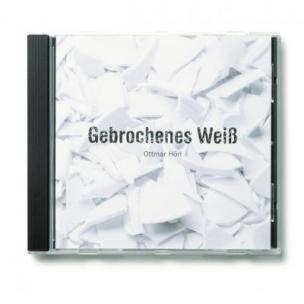

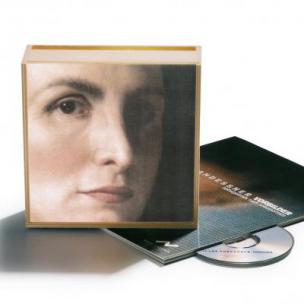

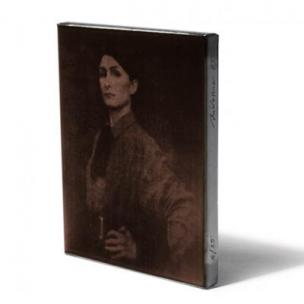

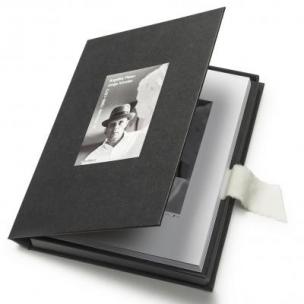

Wild Thought,

two-part portfolio by Ottmar Hörl,

"Rotation (photography)" / "Il Mare (painting)"

each with 10 sheets

appears at the exhibition

"Wild Thought – Johannes Brus / Ottmar Hörl"

at the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, Venice,

May 12 to July 28, 2019,

in the programme accompanying the 58th Biennale di Venezia

Edition: 15 copies per folder part + 3 A.P.

Finart prints on Hahnemühle Photo Rag 500 g/m2

sheet size 50 x 68 cm, image size 42 x 60 cm

in black leather case

Edition Minerva, Neu-Isenburg, 2019

(automatically supported translation)